On No Tags 25, we meet Jonny Banger: T-shirt hustler, avant-bootlegger, visionary rabble-rouser, DJ battle champ and bossman of the anarchic anti-fashion brand Sports Banger.

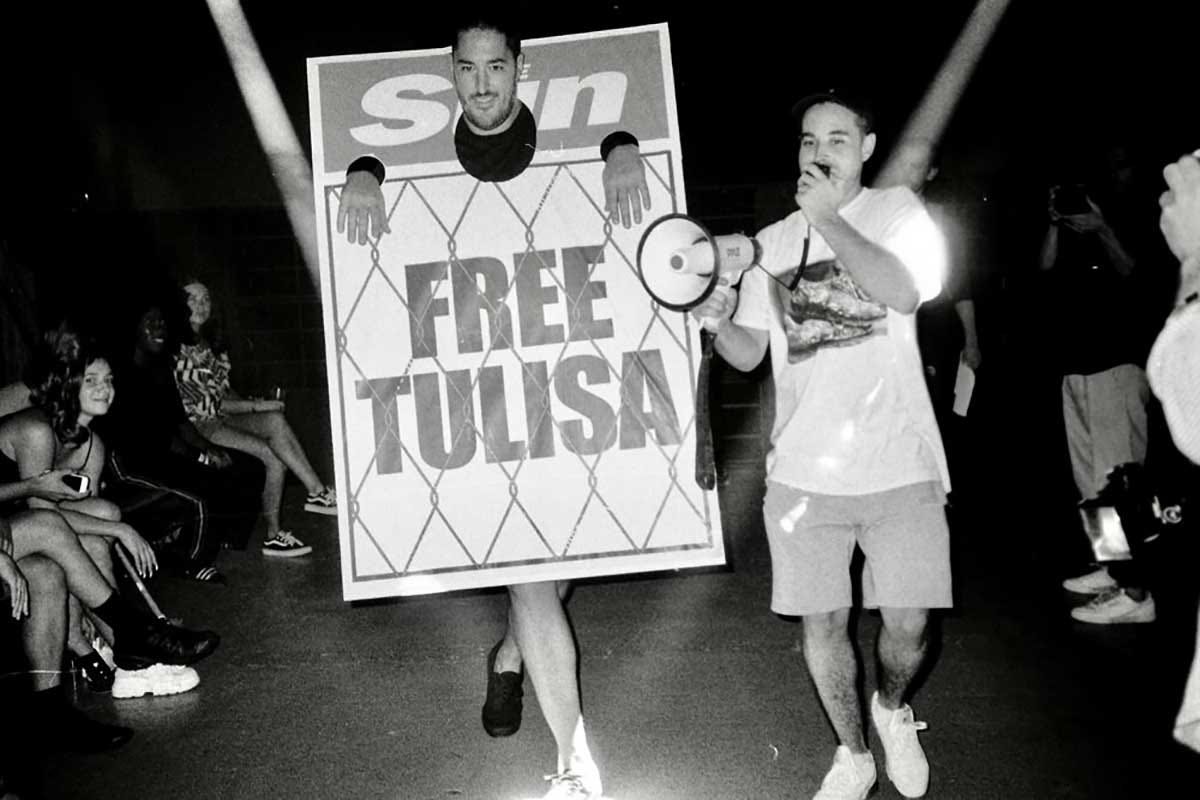

From a certain angle, it can seem like the clothes are the main event at Sports Banger, from the original Free Tulisa tee and bootlegged NHS logos to wearable inflatables and a Chanel toilet seat headpiece. Naturally, Jonny has been asked a lot of questions in previous interviews about his designs and his philosophical take on bootlegs and infringement. But there’s another side to the Banger story that hasn’t been excavated: obviously, the music.

Flipping through Sports Banger: Lifestyles of the Poor, Rich and Famous, the book that charts the first decade of the project, you can find musical references on almost every page: pilfered record label logos, Skepta in a postie’s hi-viz jacket, descriptions of his studio’s fine-tuned sound systems, playlists of tunes that inspired the Sports Banger runway shows, and even allusions to Jonny’s previous life in the UK rap scene.

We invited Jonny to go deep into the musical side of his story, from tape packs to free parties to the “shit mix jar” that collected fines in the first Sports Banger studio. He told us about his teenage years as a scratch DJ, his previous life as a club booker on Brick Lane, his ravey links with Swamp 81, School Records, Shangri-La and his own Heras label, and how he finally fell in love with free parties. And, most exciting for our resident KLF dweeb, he gave us a hint of what to expect from Sports Banger’s forthcoming collaboration with K2 on the People’s Pyramid.

It’s been a wild ride, and he’s got the stories to prove it.

If you enjoyed this big fat interview episode of No Tags then we implore you to press all the buttons and like, rate, review or subscribe on your podcast app of choice. You can also support us in a material manner via our paid tier. It’s £5 a month, and it helps us keep doing whatever it is we’re doing.

Chal Ravens: As of 2024, what is Sports Banger?

Jonny Banger: I still don't know. I've been trying to work that out because we did the book to summarise it, but I kind of get nowhere. I think I like that fact that I can't explain it properly.

Tom Lea: Is there anything it's specifically not?

Jonny Banger: I always say it's not a clothing brand. But there's contradictions all over the place. The back of the book sums it up best: "T-shirts, bootlegging, rave, fashion, pop culture, art, DIY, anarchy, politics, class, activism.” That is the world of Sports Banger.

Chal Ravens: We wanted to talk to you about the entire Banger universe, but particularly about all the ways that music infiltrates and shapes the project. You get asked about fashion a lot, about fashion shows, about bootlegging and politics. But we thought we hadn't read enough about the music element. How important is music to Sports Banger?

Jonny Banger: It’s what it all comes from – all the T-shirts, the fashion, everything. All the T-shirts started in the raves, in the gutter, and then they worked their way up into pop culture and fashion and all this kind of shit. But it's so important, even in the sense of the fashion shows we do, the way we curate the music. All the clothes are made to the sound of the records, so the shows only really come alive when we start pulling these tunes out.

Chal Ravens: Do you mean that the outfits and the tunes are meant to go together?

Jonny Banger: Yeah, we curate it that way. Like, this is an inflatable or bouncy sort of look we've got going, so then we marry that up with a track, and then that tune dictates the rest of the clothes – a bit more colourful, this and that. There is a colour to the tunes. There's a load of layers and levels to the shows, and the music is the most important thing within that, I think. Obviously it’s the people, the clothes – but actually it's the music which brings it all to life.

Tom Lea: Could you compare Sports Banger to an indie record label, in the same way that an item in the Factory catalogue can be almost anything, and it has the Factory catalogue number?

Jonny Banger: We started to look at Sports Banger more as a publishing project, where we have ideas and find the best way to publish that idea, and that might be a record or it might be a T-shirt, or it might be a fashion show or it might be a book. And that excited me, to think about it like that. Some people drew synergy with Soul II Soul and the work that they did with T-shirts and having a shop and all that kind of stuff.

Tom Lea: I'm not really familiar with that, did Soul II Soul have a…?

Jonny Banger: Fuck knows, someone told me about it and I agreed. [Laughter]

Chal Ravens: It’s the idea of being a sound system first but pushing the ideas into other products, maybe.1

Jonny Banger: Yeah. We're in our second studio now and the beating heart of it is the sound system we built. It’s that thing where mates or DJs or producers pass through, they play their new tunes and test them on our sound system. Or you're trying to do some work and someone's coming in for a fucking mix, you know? But it's nice. I came from a music space where I can walk in a studio and I know what the different equipment is, but when I first went into Tottenham Textiles, which was on Seven Sisters Road, it was like being in a studio where you've got all these overlockers and sewing machines and that kind of stuff. It's like an ideas house, there's shit everywhere, loads of colour. You walk in a [recording] studio, you can make some music. You walk into our studio, you can make anything. And that's fun.

Tom Lea: In the book, the way you talk about the sound setup in the studios is almost like someone describing a venue.

Chal Ravens: There's quite a bit of space given over to describing the exact audio spec of the studio.

Jonny Banger: Yeah, we had to get the details in, you know – what woofers did we whack in that? With a Formula Sound mixer, all this kind of stuff. It remains the beating heart of everything we do. And then the exciting thing for us was getting to soundtrack what the clothes sound like through our record label. Because people might have an idea of what a Sports Banger label would sound like, and I think we wanted to set the record straight. It's not a throwback rave sound. It's not jungle, it's not this, it's not that. The releases are pretty much across the board. The one thing it's got to be is fucking good.

Chal Ravens: We should talk about the Sports Banger Mega Raves. There might be people whose main encounter with Banger is at a Mega Rave, or at the Glastonbury Mega Rave, which you've done... twice?

Jonny Banger: Three times opening Shangri-La [a stage area at Glastonbury]. It's like the opening ceremony.

Chal Ravens: Tell us about the first Mega Rave then, why did you put that together? Was it at The Cause?

Jonny Banger: Yeah. I live in Tottenham and The Cause had just opened in that Ashley House space, and I knew Stuart [Glenn, club owner] from when I was doing a night at a place called Tipsy Bar on Dalston High Street. We did a night called Costa Del Wallop and the headline was always four shots for a tenner. One laser. We had the DJs underneath. We had mad lineups and it was always free entry. Then I just found myself at The Cause, which had maybe been open a month, and I was like, ‘What the fuck is going on here?’ It's DIY, like... there was a vibe. There was potential.

Chal Ravens: Every time you went back to The Cause they'd have found another room. A wall had been knocked down or something had changed.

Jonny Banger: It was bananas. I was in the rave like, 'What the fuck is going on here? This is great, I only live around the corner.' And by the time I'd left the venue I'd already pencilled in a date and booked the lineup. I was texting people from the rave like, '[DJ] Zinc, do you want to play this date?' So I was there, I venue-reccied it, booked the whole lineup, job done.

But the first Mega Raves… basically I'd just done a deal with Slazenger, which was the Slazenger Banger collection, and I wrote into the contract that all marketing money was to be spent on billboards and free raves for the people. So I'd book a Mega Rave lineup and I'd pay all the DJs their standard fees, but I wouldn't [publicly] put them on the lineup. It'd be like, put your faith in the Mega Rave. We put the lineup on the walls on the day. We had some fucking mad lineups. We did Mega Rave number one, number two, number three – we sort of completed the trilogy and then killed it off.

Chal Ravens: Was that the end?

Jonny Banger: No. These were at The Cause. We resurrected it on Halloween with Neil Landstrumm, Paranoid London, Jerome Hill, 187 Lockdown...

Chal Ravens: But you have done one at the new Cause [in Silvertown, East London]?

Jonny Banger: Oh, we're up to number 12 now. I might kill it off again. I don't know.

I remember, it might have been the first one, we did a free barbecue for everyone and we had all these Slazenger Banger slippers which are based on a Reebok Classic, because you couldn't buy them in Sports Direct anymore because they'd cut off the supply to them and they were now like £65 quid in Size, and Reebok Classic was cool again or whatever.

So we made these slippers and we didn't end up selling them but we just hung them all around the venue, and if you were there to the end you’d get a pair of slippers. But basically everyone just took pairs of slippers and they became like their own currency in the rave. People were swapping slippers for pills, swapping slippers for tickets to go ice skating and shit. I was like, what is going on here?

Tom Lea: I want to go back a little bit to the Sports Banger studios and music being at the heart of them. The vibe I get is that you've always got people passing through, musicians or otherwise. Does it double as a social space as well as a studio?

Jonny Banger: Mmm, nah, it's not like a surf shack... It's a studio space we work from. It's got a shop space as well, but it is our workspace, and you don't really want to shit on your own desk too many times. But also you do have to remember to have fun.

Tom Lea: ‘Too many times’ does make it sound like you've shat on it in the past.

Jonny Banger: Yeah, yeah. It can get a bit carried away. But the whole Sports Banger journey has been... it was so fucking ramshackle and headless for the first however many years – more headless than people would imagine or think, the things that were going on and just how it was run and that. But the journey, as I've got older and enjoyed the work [more], I've got better at it.

Tom Lea: Can you tell us about the Knocking Shop days and the Shit Mix Jar, because that does sound like a really good time.

Jonny Banger: So the book is written in four sections. The first section is Bedknobs and Bootlegs, that's when it started in the bedroom, with all this stock there and all that kind of shit. The second section is the Knocking Shop, when we got our first studio on Seven Sisters Road. It had just been shut down by the SO15 Terrorism Squad [part of the Met Police’s Counter Terrorism Command] and I ended up going there with my mate Matt Harriman. I was like, ‘Look, come and look at this space with me.’

Tom Lea: So what was it before?

Jonny Banger: It was an Anatolian cultural centre, and when we went in there was like a shrine to fallen fighters, Kurdish freedom fighters. We were signing an off-the-shelf tenancy agreement and Matt's looking at me like, ‘Another fine mess you've dragged me into…’ We're signing this thing and we're flanked by portraits of Che Guevara and Tito. I was like, ‘What the fuck are we doing?’ Horrible mauve walls, the worst fake wood laminate flooring. But it was a joy. We had a space. Then we got to work, everyone pitched in to strip it out.

It was kind of awkward when a brothel moved in upstairs and the only buzzer which worked in the building was ours, which said ‘Banger’. And it was a shared doorway as well. You're just constantly opening the door like, 'Uh, it's not really this one, but if you press that buzzer...' They used to work out of two different spaces, one on the corner and then here, so you got to know the madam. Everyone just let each other live. And it's a joy to be on Seven Sisters Road directly opposite Sid the Snail. Anyone in North London knows the snail, which was painted in 1976. Opening your door or shutter every day and just seeing that, it's like… yeah, we're gonna be alright.

Tom Lea: When you talk about everyone chipping in and stripping the place, have you always been one of those people who's really good at roping together loads of mates to make something happen?

Jonny Banger: I think so. I don't have many skills. That is literally my one skill, because people have all these amazing skills and talents, so it's like, ‘Look, if you do that and you do that, we're good, right?’ So yeah, I suppose I’m a bit of a rabble-rouser. If you can get people down to a pub, you can get them down to anything really.

Tom Lea: It’s like when Jack Grealish was asked what he'd do if he wasn't a footballer, he was like, ‘I'd be a promoter, because I'm just good at getting people out.’

Jonny Banger: Yeah, but I wouldn't wish the job of a promoter on anyone. I actually hate promoting. There's a reason you haven't seen Mega Rave up and down the country, or Mega Rave as its own festival. The Mega Raves are very much, like, pick and choose. We try and make it free. The only real Mega Rave we're doing now is the Glastonbury thing, but if we do it I always try and make it free, or just do it right, because it's not nice, the promoting game. People getting fleeced left, right and centre. You don't wanna fucking add to that. Agents. Fucking this, that, egos, bollocks.

Tom Lea: It's comfortably the most stressful part of working in music and running a label for me – promoting parties.

Jonny Banger: Promoting is just fucking gambling, anyway.

Tom Lea: So much can go wrong on the night. There's so much that's out of your control.

Jonny Banger: And the chances of you booking a lineup you like and no one turning up are pretty high.

Chal Ravens: You mentioned Matt Harriman. What's his role in the Banger universe?

Jonny Banger: Carpenter by trade, semi-professional DJ for life. He's the one who instilled me with confidence to be able to do any of these things. You're taking over a space and you're like, ‘Right, what's my credit like? Matt, can you back this?’ And when it comes down to building things, electrics, he can fucking do it all. You gotta have handy people on your team. And more than that, he's really defined the sound of Sports Banger. He encapsulates what Sports Banger is musically, and by building shit and knocking shit down.

Chal Ravens: What's his DJ name, so that people know?

Jonny Banger: DJ Smash Hits.

Tom Lea: Was there someone in particular who birthed the Shit Mix Jar, through clanging so often that you felt like there needed to be a system?

Jonny Banger: I can't remember how it came about but it'd be when someone's really fucking clanging it [while DJing in the studio] and you just look at each other, like, 'Oh...' So we instigated a Shit Mix Jar. I remember Mumdance coming over for a mix and he just put 20 quid straight in the jar. [Laughter] But it was good, we'd just go and buy booze and fags with it. Also there was a rule where if there's just two of you, it's alright. That's practice. If there's three, get your quids out.

Chal Ravens: We know that you did some MCing on radio shows before Banger – you were on Itch FM, which is a hip-hop radio station. Tell us about that, because it doesn't connect so readily to all of the other music.

Jonny Banger: I did work experience at a record shop in Colchester when I was about 15.

Chal Ravens: A dance music record shop?

Jonny Banger: Nah. Well, if you go back-back, my room was covered in flyers from the age of 10 from Rapture Records in Colchester, because you follow what your brother does, and he'd given me a Mindwarp tape pack for my 10th birthday, with Slipmatt, Sy, Dougal, Ratty [on it]. Kind of happy hardcore.

Chal Ravens: And Colchester is happy hardcore territory, presumably?

Jonny Banger: Yeah. There was a lot of original warehouse raves and that kind of stuff around there. But also a lot of original hip-hop stuff down there as well. I think the university used to host KRS-One back in the day. They had Colchester Arts Centre there, obviously The Prodigy are from Braintree, all this kind of stuff. And essentially hardcore is just fast hip-hop.

So I did work experience when I was 15, but I was doing the Battle for Supremacy [DJ battle championships] and got to the semi-finals at the Scala when I was 16. They called me Newborn 'cos I was the young one of the crew, and I'd DJ battle. I was gobby and I'd just diss everyone on the records. Basically from 15 I was a DJ. The elders would sort of like, raise me. And because my mum had died I was looking for something, and I'd just go around the elders and smoke in their bedsits and sheds. So that was my first entrance into counterculture. People were making zines, putting on nights. Places like the Oliver Twist, they had DJ battles down there.

Chal Ravens: What kind of records were you DJing in battles?

Jonny Banger: I'd sticker up all my rap records, like Ultramagnetic MCs, Cool C, all this kind of stuff. In the battles a lot of people would put on a scratch record, but I'd have all my rap records stickered up. I just used to diss people with all these snippets of my rap records. All that sampling of hip-hop, the sampling of bootlegging and all that, it kind of makes sense looking back.

Then I saw some of the older kids from that shop just get a student loan and fuck off to Brighton. So I fucked off and did a music production HND at Eastbourne, which was fucking awful. I lived in Eastbourne for a year and worked in [a record shop] called Sanity. You were told to upsell CD cleaners at the till and shit. And I started doing a night down there called Beer and Rap. I was down there and making noise and then I was onto the warmups for all the big shows. I supported Public Enemy...

Tom Lea: You were that guy. I feel like every city has that one guy that warms up for all the big rap shows.

Jonny Banger: Yeah totally, I'd be at their hotel and [Public Enemy members] S1W are putting me in armlocks, it was wicked.

Chal Ravens: How old were you, 18?

Jonny Banger: Yeah, 18 or 19.

Chal Ravens: You mentioned the tape pack that your brother gave you, which seems like a formative moment. Were you going to raves at the same time as being into hip-hop?

Jonny Banger: In Colchester I was too young, but I'd be DJing at the Fanaus & Firkin, next door to the Hippodrome. New Year's Eve, seven til eight slot. It would always go hip-hop and then drum and bass. That was it basically.

Chal Ravens: Where were you going out in London when you moved there?

Jonny Banger: Herbal, Plastic People, there was the T Bar…

Chal Ravens: These are the sort of Shoreditch highlights of that era.

Jonny Banger: I worked on Brick Lane at the Vibe Bar, opposite 93 Feet East. I remember Rhythm Factory and all that shit.

Tom Lea: Brick Lane is this weird forgotten part of London raving history. I remember when I first started going out when I was old enough, it was 93 Feet East, Vibe Bar, Cafe 1001. I was always on Brick Lane. People talk about Shoreditch but there was loads of stuff going on specifically on Brick Lane.

Jonny Banger: Fuse was down there. My bosses used to look out the window and see this massive queue down the street, and they're like, how do we get some of that? I was like, ‘Well, you got to put in a Function One, and you've got to get rid of the funk trumpets on a Sunday, and I can whack in some DJs for you.’ And they did that. So you got Fuse over the road and basically anyone that didn't get into Fuse was coming to Vibe Bar. We might as well have just called our night Refused. We were booking that every Sunday and had all our mates on it as well. Nick [Harriman, one half of] Dusky, who is Matt's younger brother, we used to roll around with a big old gang. I hosted for Marcus Nasty quite a few times. Actually, the first gig, and maybe the only gig he ever brought his parents to, was the night we did at the Vibe Bar, so I met Mum and Dad Nasty, which was a joy.

Tom Lea: First time I ever did Rinse FM was on Marcus Nasty's show and I was terrified. Absolutely bricking it. I'd never DJed on Rinse before and I was just petrified, Marcus watching over me.

Chal Ravens: Why did you move away from DJing if you were that good at it?

Jonny Banger: Couldn't be arsed. It wasn't the sound I was into. For my birthday the other day I got...

Chal Ravens: Happy birthday!

Jonny Banger: Thank you very much. 40! I started Sports Banger when I was 28 and that's a good age to start something. You've done enough and seen enough, and you can have an opinion on things, but also you're still sprightly enough and young and dumb enough. It's the perfect age to start something. And then 12 years later, you get to this age, you're like, what the fuck's happened here?

But basically, my mates got me this record box – handmade, Matt made it – with 40 records from 40 mates. I could cry now talking about it. Everyone had picked one. Some people had sent them from abroad. The breadth of music in there is amazing, a stunning collection. I was like, wow. And then I was just like, is this it, is this the midlife crisis? Am I gonna fucking start DJing again? And I did DJ the other night. It was fun.

Chal Ravens: So you were working at Vibe Bar, programming nights – what else went on between that moment and starting Banger?

Jonny Banger: Five years I was there on Brick Lane. The whole original team I started with had changed and everyone had been forced out. I was the last one there at Vibe Bar. No one could work out what I did and no one knew how to get rid of me. I had just had enough, so I quit. And then I was depressed and skint, and it was my birthday so I made myself a T-shirt – you know like you get yourself a present sometimes? I made the Free Tulisa T-shirt and it went from there.

Chal Ravens: So almost seamless, actually, from one thing to the other?

Jonny Banger: It was probably two months. Matt, who I lived with at the time, and his girlfriend went away on holiday worried about me, skint and depressed. They went away for a week, might have been two, and by the time they got back I had money, a new business and a girlfriend [laughs].

Tom Lea: So you made the Free Tulisa T-shirt for yourself, and you were just wearing it in raves and people were like, ‘I want one’?

Jonny Banger: I was just wearing it. You walk through the streets and people are looking at it and nodding at it and wanting photos with it. I was like, fucking hell, the power of the T-shirt! When I did Beer and Rap I actually did Beer and Rap T-shirts and I sold a shitload of those. I did that Free Tulisa T-shirt, and I'd met Artwork on top of a mountain a few weeks previously...

Chal Ravens: Sorry, where?

Jonny Banger: Snowbombing [ski festival, in the Austrian Alps]. I was basically trying to fly a kite on top of a mountain in shorts and Arthur was like, who's that idiot? He's going places, that kid. [Laughter] When Arthur was doing Art’s House, that one-day festival, he would get me to do the merch for it. I'd have this whole merch tent and I'd print his face on everything. I printed his face on tea towels, on pillowcases, loads of stuff. He didn't get a cut of any of it. I printed his face on a kite as well: 'I'm so high'. I'd just go up to him with a massive wad of cash like, 'Arthur, this is how much your face is worth.' He's like, 'Yeah, cheers Banger...'

Tom Lea: How did you end up on Rinse FM?

Jonny Banger: So Jan [Francis, AKA graffiti writer] Aset, rest in peace, him and Loefah set up School Records as a sister label of Swamp 81 for some of the [new] sounds which were coming out, which was your Duskys, your Palemans… They set up a School Records show on Rinse and Klose One was the DJ, and he was like, 'I want Jonny to host.' I didn't have a smartphone and I didn't have Twitter or anything then, and I had to have a name for it. Okay, cool – Jonny Banger. So Jonny Banger came before Sports Banger.

Tom Lea: Was that your nickname before? Or did you just make it up for the show?

Jonny Banger: Yeah, we were in the cab and Ruairi [Klose One] was like, 'I'm gonna set you up on Twitter. What should we call it?' I don't know, uhh – Jonny Banger. He called me that.

Chal Ravens: What I really like about the Banger story is that the characters stick around. You've had a lot of people hanging around for a long time and becoming embedded in new things in the project. So Klose One now runs the Sports Banger label, Heras. I guess it's an obvious step for you to start a label, but what was the thinking behind actually getting it going?

Jonny Banger: I'd wanted to do a label for ages, but I wanted to do it properly, not just a label that's not worth the paper it's written on. I didn't want to stop-start and all this kind of stuff. Also there's a reason it's not called Sports Banger Records, because I think that just sounds shit. [Laughter] 'Cos if people know you for clothes and T-shirts and stuff and then you're doing records, it seems like an afterthought.

I was surrounded by Heras fencing at a rave in south London somewhere with Matt. I was like, ‘I fucking love Heras fencing.' He's like, 'Yeah, it'd be a great name for a record label.' 'What would it sound like?’ ‘What the fence looks like.' So that became a thing.

We'd send a load of images of Heras fencing to producers and go, ‘Make something that sounds like what this looks like.' And they'd go, ‘Oh, yeah, I get it.’ Because producers can get themselves stuck, and if you approach it in a different way – it's hard, industrial, metallic, a design classic, built for purpose, all that. So we approached the project from that standpoint.

I got in from a dance one morning and I heard this voice on the other side of my door, and I opened it and it's Paul Woolford. He's just ordering a cab and he's like [adopts Yorkshire accent] 'Cancel that cab.' He put the phone down and I was like, 'Yes mate, I wanted to talk to you actually. I want to do this record label and these are the sort of sounds I want to reference, this is the soundboard of it.' And he's like, 'Yeah, cool. I completely get it.'

Devon Analogue Studio was just starting up, and Paul set it up so that we could go down there for a weekend with Matt Playford, me, Tommy D and himself, and we would make a record. That was the record COOP, which is kind of based on a pigeon coop – members come in and out. Quite avant-garde when you listen to that record – it's like UK electro drive-by music. We made that record and sat on it for ages, it didn't really make sense.

Then Neil Landstrumm randomly sent me a load of tunes. They're not throwback, not retro, they're Landstrumm future hardcore. I picked what I wanted, and then we put that out as the first record. That enabled us to put out the second record [COOP]. It kind of made sense then. And we continue now. We've got a load of releases, the next 10 lined up, [including] a compilation double gatefold vinyl thing. We've got some white label singles, we've got digital bits, we've got an album from a new artist.

Chal Ravens: What is it that makes Heras a musically cohesive sound? You were saying it's not necessarily what people might think that a Sports Banger label would sound like.

Jonny Banger: I suppose we will release house and techno and hardcore and electro, just across the board, but also curate it in a good and interesting way. The artwork for every record is a Heras-made object or features something Heras – these things which have been through our fashion shows, like the Heras corset which is made out of Heras [metal] plates. If you look at the artworks, these are all things which have been made in our studio.

I don't really see a lot of music people working with [visual] artists to make things happen, which has been quite a joy. I just got brought on as a creative director for The Blessed Madonna album. She asked us to do all the artwork and brought in her whole archive. We're talking about the Midwest, where she came from, and like the tent revivals and laying of hands and all this kind of stuff. It's fun when you get to do that shit.

Tom Lea: You were saying early on about doing the Sports Banger fashion show, where you would design costumes to suit the tunes that were being played. And then you've got the opposite happening with the Heras label where you want to make music that sounds like the object.

Chal Ravens: Those playlists for the fashion shows, which are in the book, are slightly surprising. It's not just loads of old jungle and hardcore – it's Bergsonist and B33K and DJ Deeon, and more kind of gay sounding records, more colourful and unexpected in different ways. So I think there's a sense of it being, as you say, not a throwback, but chewing up all of these influences.

Jonny Banger: It is a whole world. The fashion shows are part manifesto, part total artwork. They're the most amazing things to do, they get me so excited. We haven't done one for a couple of years because they cost a fortune. Hopefully we'll be doing one in February. The working title of that is Bangtazia, and that's to really blur the lines between fashion show and rave.

Chal Ravens: At some point you also got more involved in free parties. Did that have any effect on how you thought about the rest of the Banger project?

Jonny Banger: Yeah, the free party thing had a big effect on me. I didn't really grow up at free parties. I went to a good few squat parties and stuff, but I wasn't immersed in the scene.

Chal Ravens: You weren't getting your trainers muddy.

Jonny Banger: No. But I was obsessed with this Desert Storm [sound system] documentary about raving in Sarajevo, when Keith Desert Storm and that go to the front line in Bosnia. There was NGOs there, operating and providing an infrastructure of sorts, but their idea was basically to go there, and what they're going to deliver is some humanity, via fucking… thumping it out.

Chal Ravens: And what year is it? Like ‘95 or something?

Jonny Banger: Something like that. They were a Scottish crew. It's a joy, like the spirit of it, and it really spoke to me. I was obsessed with it. And then me and Matt, we went to a rave in Peckham somewhere and it was shit, it didn't fulfil us. I'd got a text message from a mate who forwarded me a memorial for Keith Desert Storm, rest in peace, and it had a meet-up location, and I was like, oh my god. So I went to the Desert Storm memorial for Keith, in a London warehouse or squat somewhere.

I went down with a good crew, about 15 of us went down there and it felt like something was happening, a reunion of sorts. And I was in this rave and this kid comes up to me like, ‘Sports Banger – you make the T-shirts. What are you doing in a place like this?’ [Laughter] I was like, ‘I love Desert Storm.’ ‘You wanna come upstairs?’ ‘Look, I'm trying to find my feet, come back in half an hour.’ And he came back like, ‘Look, I want to talk to you. I've got a sound system.’ He showed me a picture on his phone. He's been doing it a long time, but he's young. He's got a proper big rig and they're a proper naughty bunch.

He wanted to unite the club kids and the free party kids. It was quite interesting because a lot of free party kids are kind of lost, in a sense, and they kind of want what the other one's got. The club kids in London are all getting mugged off and ripped off, left, right and centre, but they don't know anything different and they want something else. And actually, when you put them together that's when you get the sparks.

I watched this play out in real time. This kid I met, we started hanging out and I was introducing him to artists and stuff, and it sort of opened up his world. A couple of weeks later he was like, ‘You gotta come to our 10th birthday.’ I was like, ‘Alright,’ and he came and picked me up. I was just thrown in a van, basically. It's phone calls all the way. I was like, how involved is he in it? Because I don't know what I'm getting myself in for, he could just be all fucking talk, 'cos a lot of people are. And then, sure enough, there's a meet-up, there's these spicy blokes in tracksuits and this rig coming out in a caravan, I was sitting on a pair of bolt-cutters and I proceeded to journey with this crew to a load of raves.

And just seeing it in operation – there's no hierarchy, everyone's as important as each person. The rig might be theirs but it's nothing without the people, you know, strength in numbers and all this kind of stuff. Leaving a trifle for the landowner and a new padlock – 'sorry!' – is a joy, and it kind of opened my eyes up to how beautiful that community is. But also how insular it can be, and it's just about enjoying each other's company and opening up new worlds.

Sports Banger's always been a bridge for a load of different crews. Everyone builds these worlds into existence, but then you just end up playing to the same fucking crowd. Then when we do our fashion shows, everyone's backstage going, ‘Who's that? Who's that? He's fucking sound he is.’ Everyone's like, 'Oh my God, we're just the same!’ Yeah, it's wicked.

Chal Ravens: Sports Banger obviously has a lot of its own values baked into it – there's a sort of anarchic urge towards freedom and democracy, I guess, doing things for the people. In that sense it's anti-elitist. These values are probably the opposite of the fashion world! So I wanted to ask about how you interact with the fashion world while maintaining those values. Are there things that you've been offered that you've had to turn down on that basis?

Jonny Banger: Yeah [laughs]. Sports Banger has probably done, like, four collabs. Slazenger, Tommy Hilfiger, Lucozade. Absolut., sort of – but I just bootlegged it 'cos it didn't work out.

Chal Ravens: It's hard to tell which ones are the collaborations!

Jonny Banger: I like those as collabs. But sometimes I get the worst companies getting in contact via an agency about wanting to collab, and they're always fucking food! It's always food.

Chal Ravens: Really? Ravers don't eat!

Jonny Banger: And not this muck, either. I probably shouldn't...

Chal Ravens: Are we talking about fast food?

Jonny Banger: Yeah, the fastest. I'm just wondering if I do actually name these brands and do all that kind of shit.

Chal Ravens: We can bleep them…

Jonny Banger: Alright, so. Sports Banger, at the end of every month, we are still trying to make rent and pay wages. It's a fucking nightmare. There's no investors, no management, there's never been any investment. It's so long, everything, in the spirit of DIY. We want to make art and stuff, and then at the end of month we go, 'Oh, we've got fucking bills, we have to sell a T-shirt,’ and then we get turned into this sort of T-shirt salesperson again.

So you get agencies approaching you like, ‘Hey, would you be interested in...?’ I've had [redacted major food brand] – you can bleep that out – we’re talking about 150, 200-odd grand for what that would have been.

Chal Ravens: But what would you have made for them?

Jonny Banger: They always want fucking T-shirts. They want events. All this kind of shit. You know, [second redacted major food brand] offering 20 grand for a fucking T-shirt. No – you're on the [BDS] boycott list.

Chal Ravens: 20 grand is not even enough, really, for a multi-million pound brand.

Jonny Banger: Some people can just do these collabs 10 a penny 'cos they don't stand for nothing or no one. But we made our bed, happily. It's quite mad that people do get in touch, and it's like, why did you think that this was a good idea? The agencies in the middle are the worst though. I thought, in this day and age, that these companies would have someone embedded in their business who can actually make direct contact with the makers and creators. I thought that we would be able to cut out these awful agencies at some point, but it hasn't happened.

Chal Ravens: Does that apply to the fashion world itself, or do you feel a bit more comfortable because you know what you're making?

Jonny Banger: The fashion world is awful! It's the fucking worst! I hate it.

Chal Ravens: But they love you.

Jonny Banger: I don't know. Yeah, it gives them something else to write about.

Chal Ravens: An exotic trip to an unusual part of London, perhaps.

Jonny Banger: Yeah, we drag everyone down to our level, which is a warehouse in Tottenham.

Chal Ravens: But you're still using the fashion show as a medium, aren't you? Which plays into the economy of it, and the seasonality and all of that. It's pretty different, but you are using that as a kind of megaphone for what you're doing.

Jonny Banger: Yeah. We've been asked if we wanted to show on schedule by the British Fashion Council. We were like, no. We show off-schedule, and we call our thing Off London Fashion Week. We don't have any buyers. We don't do it in a traditional way. Until the first fashion show we did, I'd never been to or seen a fashion show.

Chal Ravens: Is there a Banger stockist, even?

Jonny Banger: No, we've never had a stockist. 'Cos I knew what stuff my tees would be stocked alongside, and I didn't want to be one of them. It's not streetwear. [For the 10 year anniversary], the only place we wanted to be stocked was Dover Street Market, so we approached them and they were like, 'Oh yeah, we fucking love Sports Banger.' 'Cool, well, we want to be the cheapest, most vibes-iest thing in here.' And they were like, ‘We've never heard that before.’ So then we stocked with Dover Street.

But it's so hard. We've watched so many brands being stocked everywhere and it all comes crashing down. Even if you look at the Matches [collapse] which happened recently, and the [fashion] houses that brings down, and people out of jobs and suppliers and all this kind of stuff. We've never had any money to actually be able to outlay on really making stuff, like our own patterns. And where's that getting made? Oh, that's going to China. We want to make everything in London, all under one roof. But then making the couture bits for the fashion show, we can't scale that up within our studio space because the price point that that's gonna be is...

Chal Ravens: Is the couture element real – do people commission things from the studio based on what's been on the runway?

Jonny Banger: We have done, for sure. But everything we make for the fashion shows, apart from the T-shirts and some other stuff, we just hang on the rail like, ‘That'll be nice to make one day.’ We have just made a collection for The KLF, with the K2 Plant Hire Ltd, they’re building a People's Pyramid in Birkinhead and they’ve asked us to curate what that ceremony looks like.

Chal Ravens: I love the KLF, and they’re an obvious artistic forebear in some ways – there’s the bootlegging in the music, and driving a truck through the expectations of what a band is meant to be. Jeremy Deller would be another one, an artist who makes work that brings people together, like an intervention in everyday life. But why don’t you just explain – so what is the People's Pyramid? What are the KLF doing now?

Jonny Banger: To put the date in the diary, it’s November 23rd. For the last five years – and this is something they’ve spoken about from years and years ago – but in the last five years it’s been put into action. So if you die and you’ve signed up for Mumu-fication, then 23 grams of your ashes get fired into a brick, and they get laid at the People’s Pyramid on the 23rd November every year. It’s gonna take til 2323 to complete. It’s in Birkinhead.

I went down to the ceremony last year. I got down to the harbour in Toxteth and there was someone in a canoe with a flare going off, the base of a pyramid getting dragged by the people, loaded onto the ferry. The ferry was in silence but with the ferry tannoy going buh-duh-bu-bu – and then it’d read out the names of the people whose bricks are getting laid that year. And it’s so absurd, but you’re rocking backwards and forwards on a ferry out in the wind going across the Mersey, and these names are getting read out, and then you realise, oh shit, actually there’s loads of people’s loved ones and family and stuff. And people whose bricks have already been laid in the pyramid are coming back again, sort of like a pilgrimage.

At one point, it was like, ‘To break the silence, shout the names of your loved ones across the Mersey’. I was rocking backwards and forwards, shouting names in my head, my mates who are dead and my mum’s name. And someone shouts, ‘Too many of my friend’s children, too soon!’ Fuck. Then you get out the other side and Bill and Jimmy are there in a ice cream truck, and the base of the pyramid gets loaded onto a forklift with a bagpipe player hanging off the side with a strobe light strapped to the top of it.

It’s going through the streets of Birkenhead with people leaning out the window like, what the fuck’s going on here? With a load of nutters following it, all in hi-viz because that’s the funeral wear for the occasion. So that’s kind of the picture of what it is, and it changes every year. Throughout the day there are so many different things going on, you had Stone Club talking about funeral rites and how pottery changed the way funerals were done, because now you could drink booze, and these vessels could carry ashes but also booze and cheese, and all that shit. There’s so many ways to celebrate a birthday or celebrate a wedding, but in death and funerals…

Chal Ravens: In Northern Europe and England, we're not very good at funerals.

Jonny Banger: Yeah. 23 grams, as well – that's probably, like, your hand. That's not all the ashes. That gets fired into brick, and they've found a permanent location for where the pyramid will stand. There's actually a manual on how to build the People's Pyramid. We've got to curate what the ceremony looks like this year. I don't know yet, but the email I sent today to everyone involved was probably one of the funniest emails I've ever had to send [laughs]. And working with them and talking with them about it is just... yeah, the meetings are like no other. The vibe is really, really electric, and it's hilarious. It's not something I've experienced within the company of any other people, or meetings or work or anything that we get to do.

Chal Ravens: The thing that I always get from The KLF, having read the excellent book about them by John Higgs, is that there's something about Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty working together that creates a force that's almost beyond their control. There's so much weirdness around the whole thing.

I was thinking about their interest in rituals and magic, and it’s very different to where you're coming from in terms of the messages that you're putting out into the world. Your politics is very real and very everyday, whereas they're doing something that's quite esoteric, I suppose, and looking into the future hundreds of years. How do you see the two projects matching up?

Jonny Banger: I mean, it sent me down a proper Discordian wormhole. Like, gimme some of that! We are very much about making things that can be otherworldly, and experiencing different emotions or presenting things in a different way. And with the state of what we're living every day, through the last 14 years of Tory government – and Sports Banger is 12 years old, you know – actually the work got more and more shouty and political. It was never meant to be like that. And actually, in them moments, I do go, 'Can't we just do something which takes us out of this world?'

The book got us to draw a line under all this work, and we can actually look to the future now. All our work is collaborative, when you see the equal sharing of ideas and everything we do. But to be able to get dragged into someone else's world is amazing, and we kind of run away with that. Like working with Gareth McConnell, the photographer, shooting our fucking DIY-made shit through his psychedelic lens. You don't see the DIY, which is actually what it is, like cut-up fucking toilet seats and stuff. But then through this psychedelic, romantic lens of Gareth McConnell it's just like, wow – those two things jutting up against each other is quite magic.

Tom Lea: It would be remiss not to talk about what's going on in the UK at the moment. We also made the observation that Sports Banger has only existed under the Tories until now.

Jonny Banger: Yeah, we've not known anything different.

Tom Lea: And as you said, a lot of your work is a reaction to that, whether it's corruption, austerity, what happened during Covid. Have you thought about how Sports Banger will evolve with a new government?

Jonny Banger: Yeah, I mean it's anyone that holds that position. Anyone in that position is to be held to account. But also the work doesn't stop there. It's even more important now, because actually, it's a different government which you could maybe lobby and actually get some changes happening. Now we have this Labour government, let's see what happens. There needs to be more conversations, and maybe it's a bit more malleable.

But it was mad, when we did that rave after the Tories were out, the kick drums just sounded a lot tougher and it felt like change, you know? I'd like to think that we'd be able to have a bit more joy. We always try and do things with joy, not to be too po-faced about everything or too activist-y. We approach it in a different way. But then, the country right now is just...

Chal Ravens: We should acknowledge that we're recording this under the circumstances of ye olde England descending into racist violence, not for the first time in recent years. I also noticed that Keir Starmer's approval rating has tanked in the last few weeks as well. It does leave you thinking, in comparison to what 1997 must have felt like, we're just not in that mood. So in that spirit, I thought I should ask: what's wrong with this country, John, and how do we fix it? [Laughter]

Tom Lea: For the record, we don't ask many guests that.

Jonny Banger: I ain't got the answers!

Chal Ravens: It almost sounds like a bit of a cop-out, but it is important to bring some joy back into our lives, isn't it? But it feels like your work is getting more and more political, in some ways.

Jonny Banger: I think information and reading and learning, and education… the class system is fucked and I think is responsible for a lot of stuff. What to do about it? I don't know. We kind of start where we are, you know? Use what we've got and do what we can. That means working locally and on your doorstep and hopefully that spreads out further. With the work we were doing, we were hoping that people would replicate that where they were. Rather than people donating to things we were doing, we were like, no, no – the idea is that you replicate this on your doorstep.

Tom Lea: Our final question is always that we ask our guests to recommend a film – but we would also like to know before that, what did Sports Banger do at the Triangle of Sadness premiere?

Jonny Banger: So I had these immersion suits. If you're caught at sea, they're like neoprene, they're all red – it's to keep you warm and dry, basically, you get them on oil rigs.

Tom Lea: You just had these kicking about?

Jonny Banger: I had about 12 of them from my mate Matt Playford, whose dad's got a lock-up down in Southampton. He's got loads of stuff, he fixes boats, and he had all these out-of-date immersion suits. I was like, 'Yeah, I'll have them. They'll come in handy one day.' We'd had them for over five years. I was looking at them going, 'What shall we make?’ and I get an email from these film people going, 'Hi, we've got the premiere of Triangle of Sadness at the British Film Institute. Would you be up for doing something for it?'

They sent us the trailer: it’s a boat and people drowning, it's about fashion and modelling and class, and all these brands are mentioned within the opening 30 seconds, H&M, Balenciaga, this kind of stuff. So I'm looking at these immersion suits and I was like, how about all these brands which are mentioned, like Prada, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, we print all their logos across this immersion suit and we'll send it down the red carpet? And they were like, 'Yeah, we love it.' The only problem then was that we needed someone to wear it. I was looking at Dom and Dom's looking at me. I was like, 'Look, one of us has got to wear it.' He wanted to come to the premiere.

Chal Ravens: Who is Dom?

Jonny Banger: I used to introduce him as my translator. He's amazing. He's been at Sports Banger for four years now. He's a joy to work with. We work really well together, but he comes from a background of actually knowing art and fashion and stuff. So when I've been making stuff or looking at stuff, or have an idea, he'll be like, ‘Do you know this reference point? Do you know this?’ I'm quite naive in that sense. I don't know all these artists or these people or these things. And that's been quite a joy to learn and read about. But I was looking at him, he was looking at me. I was like, if you want to come to the premiere, the thing is, one of us has got to wear it. And he fucking went for it. Like, fuck it, I'll wear it down the red carpet.

We went to this drinks thing beforehand and he put the suit on, everyone wanted photos with him. He had to walk the carpet with the director, Ruben Östlund. Ruben loved it. He sent us a quote for the book.

Chal Ravens: And then you saw the film. It's a perfect fit! All the themes.

Jonny Banger: We literally nailed the brief.

Tom Lea: So finally, what film would you recommend? Are you a film guy?

Jonny Banger: Yeah, yeah. Black Cat White Cat, which is [Serbian]. I can't remember the director. Essentially it's a tale of bootlegging, but it's amazing. It's a complete riot festival of a film. Play it loud, you can dance around the house to it whilst watching it. It's the best film ever.

As well as being a band, a sound system and a clubnight, Soul II Soul had a store in Camden during the ‘80s, selling their own merch including leather jackets, tracksuits and memorabilia.