Based in New York and Chicago respectively, Nick Boyd and Tony G run Sorry Records, one of the underground’s best dance labels.

Formed after the pair met studying at NYU in 2011, Sorry has been responsible for some of the most exciting and idiosyncratic music to come out of North America in recent years, including records by Basside, WTCHCRFT, C Powers, Eamon Harkin, Escaflowne and Tony’s own productions. They also run a brilliant mix series1 and a show on The Lot Radio, and throw regular parties in New York — the whole shebang.

But Nick and Tony don’t just have an eye for talent. They understand the higher purpose of a record label: to cultivate, support and nurture; to provide a community and context to artists; and ultimately, in their words, to “unify and unite”. They understand this because they understand dance music, and as this episode proves, their knowledge of its history runs submarine-deep.

With that knowledge comes responsibility, and Nick and Tony are more than happy to hold people to the same high standards that they set themselves. So as much as this episode lets them shine a light on some of dance music’s most important historical figures, they also set their sights on some of the institutions who they feel have let the side down. Crucially, though, every criticism they make, they totally back up — and they clearly come from a position of wanting to make their scene as great as it possibly can be.

We talked about the dance lineage that runs from James Brown through The Loft and beyond, the corporatisation of the underground, acid’s historical importance to dance music, the responsibilities of a record label in 2023, Boiler Room, the music press and this episode’s main theme: the network of dance music in North America that ultimately drives Nick and Tony’s mission. This is the Sorry Records story to date — but it’s also much more than that.

Tom Lea: Did you both go to [upstate NY dance festival] Sustain-Release? Or was that just you, Nick?

Nick Boyd: Just me.

Tom Lea: Did you see the baby?2

Nick Boyd: I did. I’m in a Discord channel where somebody got wind that a baby would be coming weeks before the festival, so this discourse has been just rolling. This is not for the record, but I keep wanting to go, “The baby's name is [censored]!” Like, she has a name! I know this because the mom was sitting in my chair. I’m the only person at Sustain that cares about comfort so I drag a chair everywhere I go, just to have like a home base and sit down. So a lot of random people ended up sitting in it, including the baby.

Chal Ravens: I mean, babies go to all kinds of festivals, but Sustain’s maybe the type of festival where you wouldn’t bring a baby?

Tom Lea: I don’t think babies should be at festivals. I’m quite hardline on that. Did you see the UFO?3

Nick Boyd: I had no idea about the UFO [at the time] but the video is incredible. It’s just like blackness, one little light. And then two people going like, “do you see that?” Obviously on acid.

Chal Ravens: Tom — ask some real questions, come on.

Tom Lea: OK, well one of the one of the first times I think we properly hung out in New York, we were in the Nowadays smoking area. And one of you, I want to say it was Nick, was like, “fuck De School, fuck Europe. I'm sick of this idea that the best clubs are in Europe.”

Tony G: That sounds like Nick.

Tom Lea: Yeah, right. You were just like, “the best clubs are right here in New York.” That was the first time I’d been to New York in a long time, and it was like, wow, these guys are really riding out for their city in a way that I could not convincingly do for London clubs. How does New York feel for you guys at the moment? Is it still the city that drives Sorry Records?

Nick Boyd: I’d say so. That being said, my prescription of the last year is that I think everything across the board in dance music has gotten progressively worse — just because the machine is back. The best partying I had and the best music I heard post-pandemic in a club was when we couldn’t book people outside of America. I’m New York-centric, but I’m also American-centric. This is American music.

I like house music. I like that garage spectrum through club music. And I think that sensibility of dance music that I find so foundational is like… You just can’t find it [elsewhere] in the way you can find it on the East Coast of America. But a big part of the last two years for me has been getting out of New York and finding inspiration elsewhere. Tony and I were absolutely rocked by our experiences in Detroit for Return to the Source, as well as Honcho [Campout] and going to Hot Mass in Pittsburgh. We’re not focused entirely on New York, or America, [but that’s my] personal bias. But I’ve also not really danced internationally that much. I’ve never been to Berlin.

Tony G: Yeah, for me, the last couple years, ultimately resulting in me moving to Chicago, has been a bit of a realisation that New York is certainly the best dance music environment in America, but it was also going to Detroit for Movement and going to Honcho Campout and realising that people in smaller scenes are doing really cool shit too. Realising that it’s more about this idea of the network of underground, mostly American music that we’re in. New York will always be where Sorry Records lives, I think, even if I’m not physically there. But it’s been cool for both of us to realise that it doesn’t have to be about geography. It’s about unifying people with a common purpose, which is what dance music is.

Nick Boyd: But also the touring DJs… I’m sure there’s great DJs all over, but I’m not seeing them. Because to become a touring DJ and have enough clout and money to come to New York, you’re probably a pretty business-oriented person. My favourite DJ in the world, Carlos Souffront, it’s not his day job. His day job is cheese-mongering. The best people I think are always in their own DIY scene somewhere. Like Tony said: the network. Our focus is on the network, and we’re trying to make music for that network.

Chal Ravens: My limited travels in the US have definitely given me the impression that dance music in America remains an outsider, niche interest. It attracts DIY people, weirdos, eccentrics, obviously queer communities. It’s never had its huge mainstream cultural moment the way it has in the UK or the Netherlands, and I’ve been getting my head around this idea of, as you say, the network — where every city has maybe 20 to 30 people who’ll turn up to every show. And because those people create something in their city, it becomes almost more of a mutual aid network than an industry, which is just so totally different to how things work in Europe. It sounds like that’s what you're tapping into.

Nick Boyd: Yeah, absolutely. And I’ve come to value that network way more than exposure or money, as far as the way we run the record label goes. I made a decision in the last year that I just don’t think we're going to work with anyone that we don’t know. That doesn’t mean I’m only going to work with people I already know. If people send me music and I really like it, I’ll just go, “When are you in New York next?” and we’ll find some time to hang out. At the end of the day, we’re not a business. We’re a creative community full of collaboration and I think it works best when you’re all on the same page. And also: people rule. Everyone’s so sweet, and has their own lived experience and we’re all united by this rather amorphous thing. We’re all helping each other and sharing. I love how nerdy the scene has gotten in New York. Tracklist sharing is a huge thing, which I’ve pushed for so hard. These collaborative YouTube playlists, post-festivals — just give it to me, I love it.

Tom Lea: I have this theory about what you guys are talking about with the network and why I think it’s such a struggle to make a similar thing happen in the UK or in Europe. There’s such a tried-and-tested pipeline between being a popping artist from London or Berlin and just going straight onto the European festival circuit within a year. Good on those artists, they’re making money, but I don’t think it’s good for their art, and I don’t think it’s good for scenes. In fact, it really negatively impacts scenes when the minute someone starts to pop, they just suddenly hop on this European festival treadmill. Whereas in my limited experience of going to festivals in North America — and I obviously don’t mean Sustain or Honcho here – those same opportunities aren’t there for underground American artists. I went to CRSSD Festival in San Diego and the vast majority of the line-up was non-American acts: Fred Again, VTSS, Romy, Jamie xx...

Nick Boyd: That’s [California concert company and Coachella promoters] Goldenvoice’s hipster dance festival. This is what we are up against — not EDM. EDM is not the enemy in my mind. What we’re up against is Fred Again, Jamie xx, XL Recordings, Ninja Tune. This corporatisation and selling of the underground aesthetic.

Tom Lea: This is no disrespect to anyone that was playing, but I was watching some UK artists DJing there and thinking, “you definitely don’t have fans in San Diego.” There is no reason, apart from agency connections, to be booking some of the people on that line-up over someone like AceMo, who would probably get more people through the door. It was insane to me that this festival can take place in a major North American city and barely book anyone from America. But I guess there’s a slight positive in the sense that you can just see that side of things as pure opposition. There's no, “oh, if I have a couple of popping releases on HAUS of ALTR I can be on that festival circuit,” because you just can’t the same way you can in Europe. That’s not necessarily good for people’s pockets, but it’s good for this idea of the network, right?

Tony G: Yeah, it’s insane sometimes to be caught up in the underground and feel like it’s a pretty big thing and everybody’s on the same page, and then you see that going on — just a complete vacuum, chugging away, doing similar things to you but completely divorced from your values. It can drive you crazy, but also it’s fine because it’s just like, don't think about it at all. I’m completely uninterested in that for the most part. Sometimes you have to brush up against those mechanisms a little bit, and it’s weird, but we’ll take it.

Chal Ravens: I was thinking about when I first went to New York, which was a very long time ago, and it was a very, very different place for dance music. It was before Output4 had even opened, and there was nothing on. The only thing that looked like a good night out was Horse Meat Disco — so we ended up watching people from South London play disco, which is obviously [a sound] from New York anyway! I want to know a bit about where you two enter New York nightlife and what particular nights and scenes were your launchpads, because I think it’s important to recognise that the New York scene of today is pretty different even to the scene six or seven years ago.

Tony G: We both moved to New York in 2011 to go to college at NYU. That’s where we first met. But it was around 2016 or 2017 when I started to really get the dance music bug. I was making music for a long time, I was in a rock band, I was trying to make rap beats — music was always a huge focus for me. But at some point it all kind of clicked, I got into dance music, started going out, started to make house tracks and it was like, oh, this is what I’ve been trying to do the whole time. For me it was 2017, going to Bossa [Nova Civic Club] on the weekend, going to Half Moon parties... I think Half Moon Radio5 was a huge moment in New York.

Nick Boyd: I'd read Tim Lawrence's Love Saves The Day6 [and] I had gotten into Paradise Garage playlists via our friend Harrison. We would just do acid and listen to The Loft playlists. Reading that book really tuned me in, like, “what the fuck is this? I need to find these parties.” Nicky Siano was mentioned in that book a bunch. He started the club The Gallery in the 70s when he was in high school and was the first DJ at Studio 54. He’s an absolute disco legend, one of the first people to DJ on three decks. He returned to music after Love Saves The Day essentially turned folk history into written history and there was a renewed resurgence and interest in everything downtown disco. So I was going to these parties with a lot of elderly people, watching Nicky Siano play Aretha Franklin at 4am. And then the party that signed my soul to the devil of queer American techno for the rest of my life was Wrecked, and Ron Like Hell7 — the best DJ in the world still, and someone who has changed a lot of lives on the ground in New York.

Tony G: I had a project called Harmony House that ended up being the first official Sorry Records LP, me and my friend Noah Engel. We made this record, and Nick was just like, “Let me release it.” Nick was always the perfect person to run a label, he's got the chutzpah you know? He was just like, “Let me help you. Let's put this out. Let's do a label.”

Nick Boyd: The concept of the label [at first] was we do everything. I was a very diverse music listener, but we eventually needed a [more defined] purpose. My number one tip for running a label is: don't stop. Not stopping taught us a lot of lessons. We were actually working with a couple people that weren’t Tony, we were putting out some indie rock and I eventually just said, “Hey, guys, I’m sorry, I want to do all dance music now.”

Frankly, it was going to Unter8 and Sustain for the first time and being like, this is the best musical environment I’ve ever been in, but the music kind of sucks. It’s not what dance music is. Because I’d been to the disco parties. I’d read the books. I understood that [this should be about] curatorial genres, made up of many different parts. That’s literally the definition of house music and techno. That’s what Frankie [Knuckles] and Ron [Hardy] were doing. And that’s what — fuck him, but — Derrick May was doing. Techno exists because the dude played a bunch of different genres. So I thought, this “we put out everything” approach, it has a purpose now. We put out everything that makes sense on a dance floor, because good parties have all types of music being played. And also, I knew a bunch of people from disparate scenes that didn’t know each other, so I thought there was a social purpose to it, too.

Tom Lea: Something I think a lot about with my own label Local Action is where it fits in a wider contemporary club context. Who do we sit alongside? Who are our actual contemporaries? And depending on the time period, or the club trends of the moment, there are points where it feels like there’s stuff that sits nicely alongside what we do and we’re part of a larger movement, and there’s other times where it feels like we’re kind of siloed off doing our own thing. Do you guys have those same thoughts and discussions about Sorry?

Nick Boyd: It’s my internal monologue. And that’s part of the reason why we don’t want to work with people we don’t know. At the end of the day, the function and value of a record label is much bigger than sharing good music. There’s tons of good music. The support that a record label can lend to an artist is really valuable. If I didn’t believe that I wouldn’t do this work.

Tom Lea: For the record, I also made a pledge a few years back to not work with people I don’t know. I can have a phone call with them and get to know them online, I don’t need to hang out with them. But any time — and it is rare — but any time we’ve done these one-and-done records that feel quite transactional, and I’ve never quite vibed with the person, I’ve regretted it.

Nick Boyd: We want to be friends with people. Nothing’s better than growing alongside other artists. We’ve had the ability to do that with a couple people, and I think that when people associate artists with our organisation that’s the biggest compliment I can get. And like to think that at our best, when my life is stable and I have the energy and everything goes well, we’re able to do a little bit more for people than other labels around us. The goal is always to be part of a community. I don’t want to make my own and I don’t want to be on an island.

Chal Ravens: There are obviously quite a few Sorry Records releases at this point — are there any particular ones that stand out for you as important?

Tony G: I don’t want to say one of my own…

Nick Boyd: Go for it Tony! I will if you don’t.

Tony G: ‘Acid Tony’ in 2018.

Nick Boyd: That’s a watershed moment for us.

Tony G: That was the first techno record we put out. And that was the one where, for the first time, we sent out DJ promos to everybody we were paying attention to in New York and beyond. And that was the first record that AceMoMA and Dee Diggs and the Half Moon folks — the DJs we loved in New York — started to play. I heard tracks from that [record] played all around me. And it was crazy.

Nick Boyd: I cried at Nowadays. Dee Diggs played it, and I was just like, I can't not chase this feeling. It really impacted me. It was like, I’m not just interested in dance music, I want to be doing parties, I want to be all in. And also after going to Sustain I was like, I want to make all of this better, musically.

There’s two vocal records that we put out last year: XHOSA’s ‘Push It’ with the X-Coast and UNIIQU3 remixes, and Community Theater, the freestyle record we put out. Major label remixes are one of my primary interests in dance music and I wanted to bring back that sensibility, and we were so lucky to have two incredible projects from such incredible artists. And another that is really integral to the label for me is Drummy’s debut EP, Anger Start. Drummy’s our oldest music friend. I think if there’s a third Sorry Records rep then Drummy is really close. He’s a wonderful person.

Chal Ravens: I wanted to dig a little bit into ‘Acid Tony’ and where that might lead us. We were thinking about your artwork and the general chemical vibrations of clubbing these days. Do you take as much acid as your aesthetic implies?

Nick Boyd: Acid predated dance music for us. The whole time I’ve been in dance music acid has been a part of it, so much so that it’s never having a moment. Ketamine has been having its moment for like five years, [but] people have been doing K forever in New York. Look at Party Monster. That movie has a whole bit where they explain ketamine to you because it’s so integral to the story of clubbing in New York in that era. I find that acid tends to be the favoured drug of the most nerdy people in terms of music, as well as a really good thing for poor American ravers.

Chal Ravens: The best value drug there is, per minute.

Nick Boyd: I’ve had a moment again with the drug after not doing it for a while in the last year, going to The Loft and taking Grateful Dead acid that our friend gives us. The Loft in general has been a huge influence, for me. I didn't go for many years, I would just listen to the music with my friends. And then when I finally went, it shocked me how alive it was.

I’ve gone a couple of times in the last year, including with Tony, and it’s really hard to explain just how life-affirming that ritual is. I cried the first time I went to The Loft because of the food. They serve a mixture of Italian comfort food, Chinese take-out and soul food. I’m from the South, and they had fried okra, which is like my ratatouille and it was just too much. When you’re on acid you need to eat food about five hours in and that’s why they have it. It’s all built around [acid]. This party and dance music culture as a whole, as we know it, started because a guy was trying to make tapes for him and his friends to do acid to. That’s how [David] Mancuso started. I’m not a religious person but [at The Loft] I do feel as if I’m in this huge river of the history of dance music.

Tony G: Oh man, yeah.

Nick Boyd: I feel at my best when I feel that. I’ve not found that at a lot of young people events, and that’s why part of my big goal is to unify and unite. They played ‘Give It Up or Turnit a Loose’ by James Brown.

Tony G: It felt like James Brown was in the room. It felt like they were storing James Brown’s soul in that room, it was crazy.

Nick Boyd: The system sounds like a fucking concert. Before I got into disco, I took a class on James Brown at the very end of my college education which changed my life. He’s one of my favourite artists of all time. And I think that his contribution to dance music is... he is literally the monolith. He took hundreds of years of baroque European music sensibility and threw it out for rhythm. And the whole world has been dancing ever since. I’ve been talking to Tony about this for 10 years now. We’re on the dance floor, locked eyes, and I'm like, “This is what I’m fucking talking about.” Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful time.

Tom Lea: Nick, you talked earlier about growing up wanting to be a punk. The idea of selling out, certainly in the dance world over here, just seems to have gone out the window. How do you feel in general about working with brands and the corporate presence in dance music?

Nick Boyd: We’re just not a business. Why would we work with a brand? I would take some free booze for a party. If somebody asked me to do a skincare thing on our Instagram? That’d be funny, I’d do that. It’s more just, why are you saying yes to Boiler Room? Why is everyone saying yes to Boiler Room? They have an awful track record. We all know it. Every single person I know who’s worked with Boiler Room has been treated poorly and regrets it. So why would you say yes?

That decision, for Boiler Room specifically, was a thought process that led me to thinking, who do we want to say yes to? I made a list including Boiler Room. And yeah, they asked, and yeah, we said no. And then they ended up putting together the party and it sucked. Nobody had fun at it. It’s the same thing with press. The only time I look up our stats is to confirm a gut feeling [that it isn't worth doing]. I’ve been doing this thing recently, which I think people might find a bit annoying, but when people come to me for advice, like how do I get premieres and press, I just give them five alternative ways to reach out to listeners. Find a Discord channel for this small music scene that’s related to the release, and introduce yourself to them. Don’t send an email to Resident Advisor and chase them. Look up relevant radio playlists on FBi Radio in Australia, where all these freaks are on the radio, and get to know them instead.

[It comes back to] the network, you know? At the end of the day, Resident Advisor, Boiler Room, they will never be part of this network, ever. As they shouldn’t. Why are you constantly trying to reach out to them? They should be coming to the underground and funding it. They shouldn’t be curating. People don’t realise how much they’re giving to these platforms. It’s not just DJing for free, you’re giving them your brand. We don’t do parties with people we don’t know that well, so why would it be different for a venture capitalist-backed company9 that is going all over America and treating people like shit in small scenes?

Tony G: Personally, I’m at the point in my relationship with dance music where I know that this isn’t gonna be the thing that I make my money off of in life. I know that I’m probably not gonna be a touring lifer DJ who’s doing this as their job. I know that this is something I love and I’m gonna be a part of for my whole life, but I don’t have any bones about it not being how I’m going to make a living. Recalibrating that relationship is healthy for the most part, and then you can have a different perspective on things a bit. There’s good people caught up in it, there’s good people working at Resident Advisor. There’s a lot of great DJs who work there. A lot of lovely people are working for dumb institutions because we have to make money. So it’s fine. It’s not a shameful thing.

Nick Boyd: There’s a couple of clubs in New York that operate their booking policies in a much more dangerous way, in my mind. My focus has shifted from the press and more towards people booking white-centric, European-centric techno lineups in New York. Not only is it out of style but it’s completely out of line with the history of the city and the dance culture here.

Tom Lea: It’s also impractical. I’ll never fail to be astounded by people who mostly book acts from abroad when the talent is right there in their own city, and usually available cheaper.

Chal Ravens: And it’s ecologically unsound, it makes no sense to fly people in when you have amazing DJs right there.

Nick Boyd: All due respect to Ben UFO, I love Hessle Audio and I’ve enjoyed his DJing, but he played Thursday at Sustain this year. Thursday should be the locals’ night — half the people don’t even come. Why are we putting money in the pockets of people who don’t understand how special these spaces are to the audience? We could have made a local DJ’s life, we could have really changed somebody’s life. And instead we just gave Ben UFO a regular Thursday, and that’s not what I want from our underground. But I understand the impulse and I also understand the added value benefit for booking names like that. And I bring him up specifically because I think people think of him as this alternative option, but I’m sure his taxes do not look alt. New York’s always had really strong DJ talents that are locals. Junior Vasquez never played outside of New York. David Mancuso didn’t play outside of New York until Lucky Cloud brought him over [to the UK] in his late 60s.

Tom Lea: And in theory you should be able to do that. Every city should have their local heroes who don’t need to play outside that city to make a living.

Nick Boyd: Ron [Like Hell] has been playing to 1000-plus people every two weeks for the last 10 years. But it’s because he built the best queer party in New York. The Carry Nation10 are also a prime example of this. They have a party once a month that’s completely sold out, they have their own infrastructure, they bring in their own security. If you want to know what DJs are good in America, just look at who Carry Nation books and who Honcho books. I think that New York is at a bit of an ideological split right now, between people who have this approach and people who are dedicated to the scene but are also musically very UK-pilled. When I think about a rave I don’t think about the New York stop on the Hessle Audio tour. I think that, in general, there’s a lot more value in organisations like Carry Nation and Honcho and hopefully what we can achieve. And that’s always been the goal.

Chal Ravens: Final question. We’re all on Letterboxd, and I want to know what film I should watch next. What’s your top recommendation?

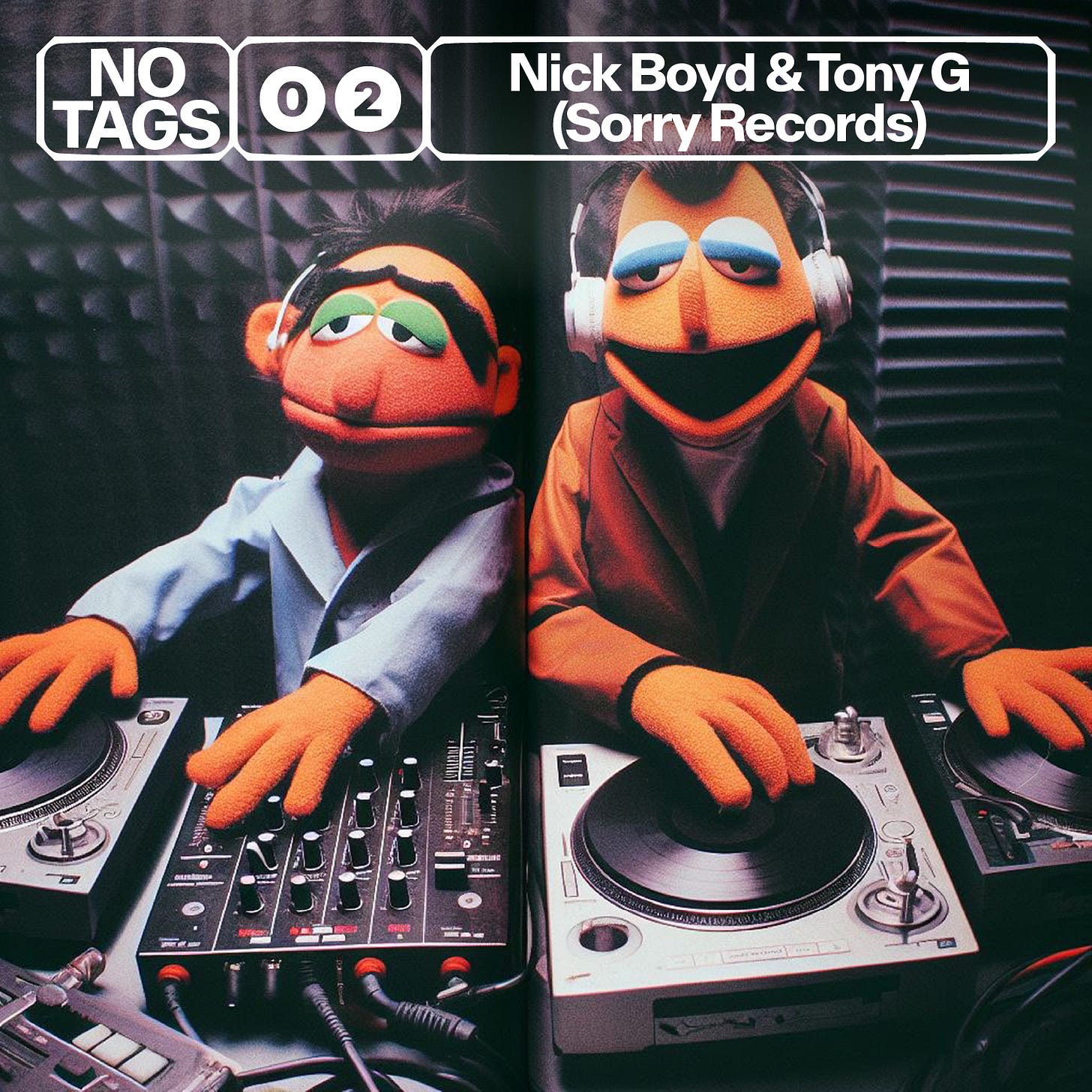

Nick Boyd: Gremlins 2: The New Batch. It’s the defining film of not only my last couple years, but our record label. All of the artwork we’ve been doing is 1000% Gremlins. The media studies shit in Gremlins 2 is so rich, it’s the most self-referential movie but also has this absolute zany quality. Our friend boxofbox always describes party vibes as either the Muppet Zone or Gremlin Zone. This is the Muppet Zone [waves hands over his head] and Gremlin Zone is when it’s like 6am and the music is evil. Like when the DJ is in a blend and they start bringing in a horn or something, way off. When Theo Parrish gets into dummy zone, or when Traxx literally does anything.

Tony G: It’s funny you should ask because in Chicago some of my friends have a DIY space that’s member-run. Me and my partner are putting on a double feature screening night, it’s going to be a monthly thing where a different person picks two movies each time. I’m doing the first one and I just watched The Straight Story, which is David Lynch's G-rated [Universal] Disney movie. I never watch wholesome movies anymore, and it’s so wholesome but also deep and lovely and still Lynchian in a lot of ways. So I was thinking that and Easy Rider would be a great double feature. My Letterboxd review [of The Straight Story] was actually just “difficult rider”.

As you’ve probably gathered, these two know their records — so here’s a selection of tracks that have inspired Nick and Tony over the years:

Paul Johnson - ‘I’m Alone Until You Show Me’

Farley "Jackmaster" Funk & Jessie Saunders – ‘Love Can't Turn Around’

Ralph MacDonald feat. Yogi Lee – ‘Laying In His Arms’ (Special Club Mix)

Lee Marrow feat. Lipstick - ‘Do You Want Me (Let's Go)’ (Extended Version)

Steve Miller Band - ‘Space Intro’ & ‘Macho City’

AceMoMa & Friends - ‘We Don’t Do This Shit 4 Free’

Gemini - ‘Le Fusion’ (12")

Bookmark the Sorry Records: Mix Series.

“A baby at sustain release is peak straight people behaviour”. Not everyone was on board with the parents who bought their baby to the festival.

Several ravers reported seeing a UFO at Sustain-Release.

Half Moon Radio, a “new age cultural institution” based in Brooklyn.

We strongly recommend Love Saves The Day, the essential New York disco history — plus Tim Lawrence’s exhaustive podcast on the subject, Love is the Message.

Truancy Volume 309 is a good place to start with Ron Like Hell.

Boiler Room was bought by Dice in 2021 after the ticketing app raised $122m in a funding round. Resident Advisor is an independent company which makes its money through ticket sales and brand partnerships.

Check this RBMA feature on The Carry Nation and “New York’s Gay Big Room Boom”.

Share this post